Brimful of Tricks

On 9 July 2014 an article was published in the Times Literary Supplement written by journalist Henrietta Foster and Austen academic Professor Kathryn Sutherland entitled Brimful of Tricks. In this article the authors make a series of extraordinary and often erroneous claims in an effort to discredit the Rice Portrait.

The context of the article was that forensic analysis of old glass negatives of the painting had revealed the signature of the artist and the name of the sitter written on the top of the painting. You can read more about this in the Photographic Evidence Section. Following the publication of this important evidence supporting the claim of the Rice Portrait, Henrietta Foster, a longtime opponent of the picture, wrote to the National Portrait Gallery to tell them that she and her friend Professor Kathryn Sutherland were going to carry out further research into the painting. The article below was the result.

We have responded to each paragraph of the article with our own points.

Brimful of Tricks

Very few people have seen the Rice portrait, as it were, in the flesh – it remains in private hands. Those who have say it is a large, almost life-size painting of a young adolescent girl in a white cotton muslin frock tied under the bust by a thin puce-coloured ribbon. The girl is wearing a gold locket and earrings, and in her right hand is an unfurled emerald green parasol.

The Rice Portrait has been exhibited 2 July - 31 August 1975, Jane Austen Bicentenary Exhibition, Chawton, Hampshire; 15-20 February 1994, Fine Art & Antiques Fair, Olympia, London; 5-8 October 1995 Jane Austen Society of North America, Madison, Wisconsin, USA; 12 April - June 2003, Falmouth Art Gallery, Cornwall. Since this article was written it was also exhibited at Queen’s College, Cambridge for the Cambridge Jane Austen Society Annual Dinner in December 2016. Kathryn Sutherland made no attempt to include the portrait in the exhibition she curated in 2017 - had she done so we would have been very pleased to allow the portrait to be displayed. We welcome enquiries from any organisation interested in exhibiting the Rice Portrait.

The Rice family, who own it, and their champions, among whom are some distinguished academics, claim that the girl depicted is Jane Austen, and produce at intervals a new discovery in support of their claim – a new artist, a new hidden message, a linen stamp or yet another family anecdote about Great Aunt Jane. Much of this evidence has been aired in the pages of the TLS, in articles and correspondence (March, April and December 1998; October 1999; May and August 2002; and most recently, August 30, 2013). So far, each new proof of authenticity has been dismissed by the art establishment, on one set of grounds or another.

We agree with this statement - as noted in the National Portrait Gallery Section of this website, until recently, every new piece of evidence, however compelling, has been dismissed by the National Portrait Gallery (NPG). (Now in 2019, faced with incontrovertible evidence, the NPG, Foster and Sutherland, all decline to comment.)

The latest proof turns on forensic evidence, provided in the first instance by a retired civil servant from the Wirral who, using a computer graphics aid known as a burn tool, scrubbed away at the surface of a digital image of Emery Walker’s photograph of the painting, taken in 1910, to discover the words “Ozia[s] Humphry, RA”, the date “178[9]” and the further words “Jane Austen” in the upper right-hand corner. This test was then duplicated and supported by a forensic crime laboratory. The findings were reported by Claudia Johnson in this journal, but they attracted little interest in the art world – presumably because, as evidence of authentication, they are far from conclusive. Emery Walker was known to favour a large format camera and a long exposure in daylight. It is at least possible that markings on the photographed canvas are the effect of the cracked glaze glinting against the flash of Walker’s camera, faults in the films of later versions, and even hairline scratches on the original glass negative, held at the National Portrait Gallery.

The forensic crime laboratory Acumé Forensic are world leaders in the field of specialized photographic imaging. You can read more about their work in the Photographic Evidence Section. The work of Stephen Cole, one of the company’s founders, is internationally recognised by criminal courts. While it may be possible to argue the writing on the negatives is not contemporaneous with the portrait, it is utterly ridiculous to claim the marks are not there at all.

It was not the custom in British portraiture of the time to scrawl a signature in such a prominent place and, even supposing these markings did exist in 1910, there is no proof they were written by Humphry, nor indeed in 1789. More importantly, Ozias Humphry was only elected a Royal Academician on February 10, 1791 and would not have been allowed to sign his works as “RA” until then. (He had been made an Associate Member of the Royal Academy on November 1, 1779 and therefore could have added “ARA” to his signature but not “RA”.)

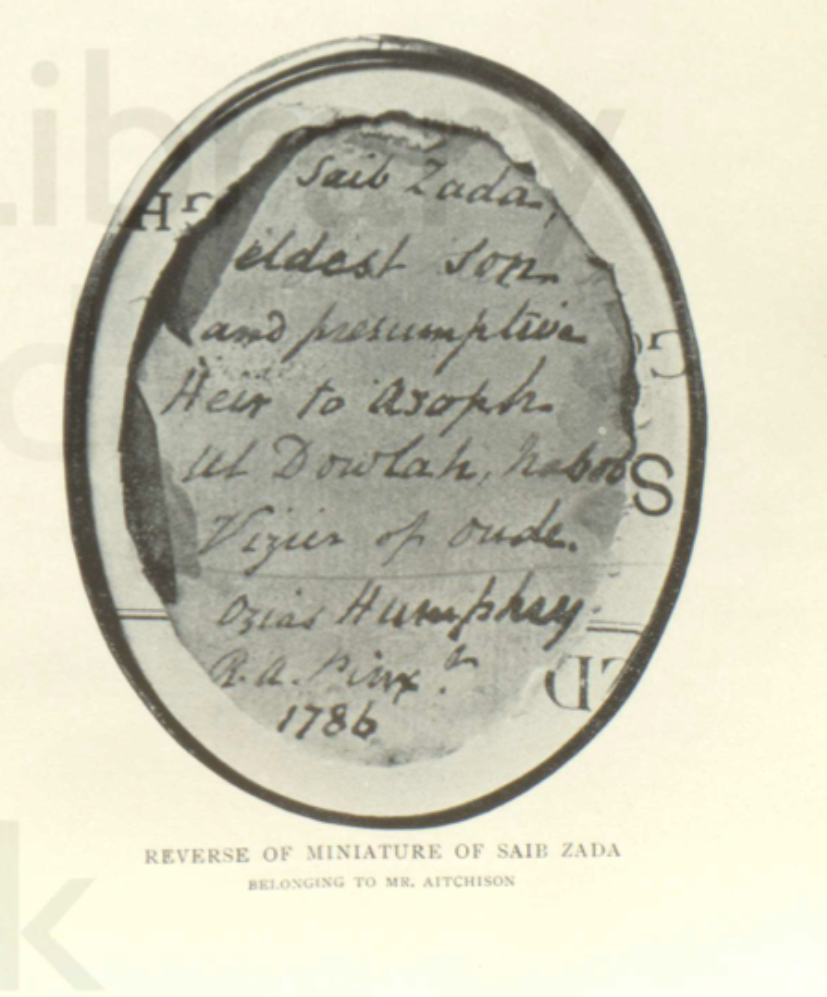

If the authors had carried out even cursory research into Ozias Humphry, they would know that Humphry was signing his paintings as ‘R.A.’ long before 1791, irrespective of whether he was formally allowed to do so. Here are three examples, one from 1780 and two from 1786.

It is worth remembering that, until the 1980s, the painting was thought by everyone, including the Rices, to be by Johann Zoffany. Madeleine Marsh, an art historian, made public the Ozias Humphry attribution (Jane Austen Society Report for 1985), supported by a valuation from Christie’s. Not one of the previous owners noticed these markings and, though the Rice portrait had been cleaned at least once before the Emery Walker photograph was taken and multiple times since 1910, at no point has any restorer mentioned finding writing in the upper right corner.

It is quite possible that when Dr Thomas Harding-Newman attributed the painting to ‘Zoffany’, rather than ‘Humphry’ that he could discern a signature and mis-read it. We are not aware of any cleaning of the portrait before the Emery Walker photograph was taken. We do, however, point out that the conservator Eva Schwan, in her conservation report agreed that there were considerable losses of glaze and fine details, due to previous traumatic interventions. That the signature is no longer visible on the painting is therefore not surprising.

But through all the arguments and counter-arguments, proof and disproofs, one fact remains, that a whole long tradition of family hearsay and recollection cannot undo: the fact that the portrait has no written provenance before 1880. None whatsoever.

We note that the unsigned and undated sketch owned by the National Portrait Gallery of Jane Austen, said to have been painted by her sister, is not mentioned anywhere before 1869 (just 11 years before the Rice Portrait), but this does not seemed to have caused any difficulties with authentication. When the Rice Portrait was given to John Morland Rice in 1882, his mother Elizabeth Rice and aunt Marianne Knight (who was living with Elizabeth Rice at the time) were still alive and both of them had known Jane Austen personally. Furthermore the Rice Portrait has firm provenance back to Jane Austen’s generation, which you can read about in the Provenance Section and the Primary Evidence Section of this website.

In 1869, Jane Austen’s nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, published A Memoir of Jane Austen, the first full-length biography; in fact, it was a joint effort by various relatives who had known the novelist. On completion, the family needed a portrait of Aunt Jane. The lack of a portrait had already proved a problem when her works had been reissued in 1833, sixteen years after her death, by Richard Bentley. The only one that her surviving family considered at the time an adequate likeness was a back view in a blue bonnet made in 1804 by her sister Cassandra. It remains in family ownership. Available to Austen-Leigh was another of Cassandra’s sketches, dating from approximately 1810 when Jane Austen was thirty-five years old. Little more than a satiric cartoon, it is now in the National Portrait Gallery. Austen-Leigh decided it was too harsh and crude, and he instructed a professional portraitist, James Andrews of Maidenhead, to come up with an improved version. Andrews prettified the sketch, making the clothes and chair grander, the face softer and its expression more compliant. The original Cassandra sketch was owned in 1869 by Austen’s niece Cassy Esten Austen, who wrote of the Andrews portrait that it was “much superior to any thing that could have been expected from the sketch it was taken from. – It is a very pleasing, sweet face, – tho’, I confess, to not thinking it much like the original; – but that, the public will not be able to detect”. The Andrews portrait became the accepted face of Jane Austen. Adapted from an engraving, it is the one we will see from 2017 on the new £10 note; a face that the nieces who knew her admitted was not “much like the original”.

Foster and Sutherland state that Austen-Leigh's biography was 'a joint effort by various relatives who had known the novelist.' It was a joint effort - but only from certain sections of the family. As Dr Sutherland explains in her introduction to Austen-Leigh's Memoir of Jane Austen, Austen-Leigh had written to Edward's daughter Fanny Knight asking for sight of Jane's letters to her sister Cassandra which Fanny Knight had inherited. This was refused. In the end, Austen-Leigh had to publish without them. It is not surprising that James Edward Austen Leigh made no attempt to contact the opposite side of the family, when they were in competition as to which side was the custodian of Austen’s memory.

In 1884, Lord Brabourne published an edition of Jane Austen’s letters, carefully marketed as a rival portrait-in-words to the Memoir of his Austen-Leigh cousin. Brabourne was the son of Jane Austen’s niece Fanny Knight and had been educated at Magdalen College, Oxford, in the late 1840s. It was while Brabourne was compiling the collected letters of his great aunt that the Rice portrait first emerged, thanks to a former don from Magdalen – to whom we shall return.

The rivalry between the family is alluded to here. Lord Brabourne published his collection of Jane Austen’s letters in 1884 and he used the portrait, recently given to his cousin, John Morland Rice, as a frontispiece for his book. Afterwards, he sold off Austen’s letters rather than pass them to the other side of the family, prompting Austen academic Robert Chapman to write to Richard Austen-Leigh, that he was ‘incensed at the vandalism of his late Lordship - scandalous old man!’

The story is that the painting was commissioned by Francis Austen of Kent (Jane Austen’s great-uncle) whose second wife, also Jane, was the novelist’s godmother. According to Rice family lore, there was a companion portrait of Cassandra and both were kept by Francis Austen, eventually descending to his grandson Colonel Thomas Austen of Kippington, Kent, in 1817. Perhaps as early as 1818, so the story goes, Thomas Austen gave the portrait of Jane to Elizabeth Hall, “a great admirer of the novelist”, who married one Thomas Harding Newman as his second wife. Thereafter it descended to Elizabeth’s stepson, the Revd Dr Thomas Harding Newman, who became a Fellow of Magdalen. He, in his turn, bequeathed it to Jane Austen’s great-nephew John Morland Rice, whom he had known at Magdalen.

The evidence is that the portrait was commissioned by Francis Austen. You can read more about this in the Provenance Section and the Ozias Humphry Section. There is also firm evidence for a companion portrait of Cassandra. You can read about this in the Ozias Humphry section and in the Primary Evidence Section. That the Rice Portrait was given to Elizabeth Hall is documented. We now know it is likely that Elizabeth Hall knew Jane Austen personally, which you can read about in the Provenance Section. There is no reason to doubt this documented provenance.

This provenance was outlined in a letter dated December 30, 1880 from Harding Newman to another Fellow of Magdalen, the College historian Dr John Rouse Bloxam. At this stage the portrait was supposed to be by Zoffany. He was the artist to whom portraits of the mid-Georgian period were attributed if no signature or provenance was available. The Rice portrait graced not only the pages of Brabourne’s 1884 edition of Jane Austen’s letters, but also Jane Austen: Her life and letters (1913), a family biography by William and Richard Austen-Leigh, which featured the 1910 Emery Walker photograph as a frontispiece.

The statement that Zoffany was ‘the artist to whom portraits of the mid-Georgian period were attributed if no signature or provenance was available’ is inaccurate. Portraits were no more likely to be attributed to Zoffany than any other artist. It also was - and is - common for portraits to be mis-attributed. There is, for example, Humphry’s portrait of The Ladies Waldegrave which took a seven day court hearing to establish it was by Humphry and not by George Romney. As Foster and Sutherland note, the Rice Portrait was not only used by Brabourne but also by William and Richard Austen-Leigh in their biography of Austen. It was also used by Mary Augusta Austen-Leigh in her biography of her great-aunt.

Between the two books, the painting languished above a fireplace in the homes of various Rices where it suffered intense smoke damage. It required cleaning in the early part of the twentieth century before the Emery Walker photograph was taken. From 1883, when it came into Morland Rice’s hands, members of the family were urged to authenticate the painting; it seems clear from surviving correspondence that Morland Rice was looking for evidence to substantiate Harding Newman’s provenance.

Our portrait has never ‘languished in the homes of various Rices’ - on the contrary it has always been a much-loved portrait. It suffered smoke damage due a fire at the home of Admiral Rice which razed his home to the ground and caused the death of his wife - a catastrophic event. It is true, however, that when Gwenlian Rice gave the portrait to her cousin she stipulated it should not be hung over a fireplace! There is no evidence at all that members of the family were ‘urged to authenticate the portrait’. Morland Rice was, we agree, attempting to establish Harding-Newman’s attribution to Zoffany but NOT the subject of the painting, which was not in doubt. His mother Elizabeth Rice, would have known if the portrait was not Jane Austen, as she had known Jane well.

In the Austen-Leigh papers in the Hampshire Record Office, Winchester, the chain of events is copied out in the hand of William Austen-Leigh, Jane Austen’s 1913 biographer, who was given access to a portion of Harding Newman’s letter of December 1880, copied out in Bloxam’s hand and passed on by him to Morland Rice on September 1, 1882. Fanny Caroline Lefroy, a great-niece born three years after Jane Austen’s death and, then in her sixties, considered to know “more than anybody about the family history”, wrote to Mary Augusta Austen-Leigh on October 23, 1883: “I never heard before of the portrait of Jane Austen . . . . I suppose Mr Morland Rice can throw some light on the matter, or is it a picture he has picked up of a Jane Austen painted by Romney but not the Jane. Mr Morland Austen picked one up & fondly believed it was her, but it was painted at Malta where she never was”. A year later, Fanny Caroline is reported in a letter of September 9, 1884, this time from Morland Austen to Morland Rice, as still struggling with “one or two difficulties” over its genuineness. She had no memory at all of family talk of a painting, and the best she could do was invent an alternative provenance: George Romney as the artist, painted on a visit to Bath, and commissioned by another branch of the family.

The quotations from the letters of Fanny Caroline Lefroy quoted by Foster and Sutherland are partial and misleading. Lefroy concludes the letter she wrote to Mary Augusta Austen-Leigh in October 1883 with: ‘I will write & ask Cassie if she knows anything of it. I am sure her father & mother never had any money to spend on portraits of their children. If it is genuine would not Mr M.R. generously allow it to be photographed? I should greatly like to see it.’ Foster and Sutherland also omit to quote the full letter from Morland Austen to Morland Rice in September 1884, in particular, they omit the following paragraph: I thank you very much for your interesting letter, which puts the matter in a very different light. I saw Miss Lefroy yesterday. She knows more than anybody about the family history. She knew before of the portrait in your possession. Except for one or two difficulties, she would have no doubts about its genuineness’.

The difficulties pertain to the mistaken attribution to Zoffany. Morland Austen records that Fanny Caroline Lefroy notes that ‘the date on your picture is (she thinks) 1788 or 9,’. Zoffany was known to have been in India at this date. We now know the painting was by Ozias Humphry, who came back from India in early 1788.

Even at the time, it seemed extraordinary to some that a family as socially aspiring as the Austens should nowhere have mentioned the fact before 1883 that their eminent ancestor had been painted by one of the great portraitists of the age. Elizabeth FitzHugh, Morland Austen’s sister, also suggested that the painting was of another Jane Austen, the novelist’s second cousin and almost exact contemporary, whom she knew as Aunt Campion.

The Austen family destroyed almost all family correspondence. Very few letters remain and so we have no idea whether the portrait was mentioned within the family before 1883. It is not possible that the painting could have been of another Jane Austen - as indicated above, Elizabeth Hall, an early owner of the portrait probably knew Austen, certainly close members of her family knew Austen. Furthermore, John Morland Rice’s mother and aunt, nieces of Jane Austen and alive when the painting was given to him in September 1883, had known Jane Austen personally. It is therefore not possible that this was a case of mistaken identity.

But no one outside the family was much interested until in the 1930s the National Portrait Gallery began looking for a portrait of the novelist to exhibit. There was considerable pressure from J. H. Hubback, the grandson of Admiral Sir Francis Austen (Jane Austen’s brother), for the NPG to endorse the Rice portrait.

While it is true that it was in the 1930’s that the National Portrait Gallery began looking for a portrait of Jane Austen for their Gallery, the suggestion that there was pressure from John Hubback, grandson of Admiral Francis Austen, for the NPG to endorse the Rice Portrait is completely untrue. It was the NPG who began the correspondence not Hubback and there is no suggestion whatsoever of any ‘pressure’. One wonders what ‘pressure could possibly have been brought to bear by the elderly Hubback against ‘Imperial Hake’, as the Director of the NPG was known. It is clear from the correspondence that the NPG believed the painting was of Jane Austen. It is also clear they were displeased they could not acquire it. They asked - and were granted - first refusal should the family ever decide to sell the painting, which at that time was entailed, as Hubback informed Hake at the time.

The head of the gallery, Sir Henry Hake, asked his friend R. W. Chapman, the Oxford publisher and Austen editor, and himself a Fellow of Magdalen College, for his opinion on the Zoffany/Rice picture. Chapman admitted to Hake in October 1932, “I never felt happy about this picture”. There was much debate as to whether the costume was really correct for the 1780s (a debate which rages on into our own day), and on May 15, 1939 Hake wrote to Chapman, “In general I believe that Cassandra’s scribble is almost the only thing done from life. The Zoffany may very likely be a cousin . . . it will always have advocates now that it has been labelled as Jane Austen herself, but as I said if you would like to come here we can tell you the whole melancholy story”. That “melancholy story” was never revealed in letters, but the gallery opted for Cassandra’s sketch, described by Chapman as “this disappointing scratch”. Chapman was now quite clear (TLS, October 11, 1941) that “the so-called Zoffany portrait of Jane Austen as a young girl is almost certainly not a portrait of her at all”; while Richard Austen-Leigh (co-author of the 1913 Life and Letters) wrote on March 13, 1950, “As to the views of my uncle [William Austen-Leigh] & myself, when engaged on ‘Life and Letters of J. A.’, he was in favour of the portrait being authentic and I was against it, – but being the younger of the two, I had to give way! . . . My own belief as to the picture is that it is not of J. A. – as indeed I have always thought” (correspondence in the Hampshire Record Office).

It was indeed R.W. Chapman who first raised doubts about the Rice Portrait. He was, as he admitted himself. ‘no iconographer’. Nor was he an expert in 18th century costume. The debate about the dating of the costume is dealt with in the Dating & Costume Section. Chapman was a friend of the Director of the NPG and as soon as the NPG purchased the ‘Cassandra sketch’ he published his lecture in which he dismissed the Rice Portrait. Richard Austen-Leigh who corresponded with Chapman, was clearly persuaded to doubt the painting. None of them were in possession of the correct facts about the picture.

Rev. Dr Thomas Harding-Newman

Who, though, was the Revd Dr Thomas Harding Newman and what do we know about him, beyond the fact that he gave the portrait to the Revd Morland Rice? Newman was born in 1811 at Hornchurch, Essex, into a rich family with interests in Jamaica and Barbados. His family owned Clacton Hall in Essex and Black Callerton in Northumberland, and he hunted with his own pack of foxhounds. He went up to Wadham College, Oxford, in 1829 and was elected a demy at Magdalen College in 1832 and a Fellow from 1846, remaining in post until 1873, when he resigned his fellowship and returned to Essex on receipt of a large increase of income. He died in April 1882. On December 30, 1880, he wrote the letter to his former Magdalen colleague, John Rouse Bloxam, intimating his wish that their mutual friend Morland Rice have the painting of his relative Jane Austen. Rice was, like Brabourne and Hubback (the picture’s late advocate), a great-nephew born after Jane Austen’s death. On Easter Monday, 1883, a year after Harding Newman’s death, Bloxam wrote to his friend General Gibbes Rigaud: “Talking of paintings Hardman [sic] Newman . . . has just sent me a full length portrait by Zoffany of Miss Austen, the novelist, to give to Rice, who is a connection of the Lady. – Rice is much pleased with it – I knew that [Harding] Newman intended to leave it to Rice, but did not, – but his nephew to his great credit has given it” (correspondence held in the Bodleian Library, Oxford).

Note that, as the authors record here, the Rice Portrait was given to John Morland Rice AFTER Dr Harding-Newman’s death by the latter’s nephew and beneficiary, Benjamin Harding-Newman (whose grandmother, incidentally, was the sister of Tom Lefroy, said to be Jane Austen’s first love).

This is all that has been revealed so far about Thomas Harding Newman; but reading through Magdalen College records and the reminiscences of former students and choristers, a surprising figure emerges, and one that casts the whole story of the Rice portrait in a different light.

In Old Magdalen Days (1913), Lewis Tuckwell, a former chorister, recalls that Dr Harding Newman “seemed to spend all his superfluous time in playing practical jokes”. Those jokes included dressing up as Dr Routh, the old President of the College “with his Georgian wig and buckled shoes”, and pretending to beat a student (in fact, a stuffed pillow) because the University commissioners were visiting and had heard that discipline was lax in the College. Tuckwell’s brother William had already, in Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), described Newman as “a practical joker; his rooms overlooked the river, and he sometimes fished out of his window”. Among his catch was a fake fish, “ingeniously constructed of cardboard overlaid with tinfoil”. William Tuckwell writes that, having similar initials to John Henry Newman, Thomas Harding Newman often received his post by mistake. Instead of returning the letters, Harding Newman would on occasion reply to them as the famous Oxford theologian and provide the required autograph. He was known at Magdalen as an expert forger. The Reminiscences continue: “an accomplished artist and connoisseur, he once, by borrowing the Cardinal’s signature, gained access to Claude’s Liber Veritatis at Chatsworth – of course in the absence of the Duke, who would have detected him”. The deception did not stop there; Harding Newman undertook to preach out of Oxford and “secured by the false initials an immense congregation, and delivered, as he used to tell the story, a sermon on the ‘Final Conflagration of all things’, which terrified many into fits”. Lewis Tuckwell concurs with his brother and he, too, remembers Dr Harding Newman as a forger of letters. W. D. Macray’s Register of the Members of St Mary Magdalen College, Oxford (1909) is damning in its summary of Newman:

“Possessing artistic taste and knowledge, he yet, by an unrestrained indulgence of humour which led to great eccentricity, practically often acted as the College jester, and it must be said that it was well for the College, and well for any parish in which he might have lived, that he never became the incumbent of any benefice in the gift of the College. ”

It should be noted that neither of the Tuckwell brothers was a contemporary of Harding Newman; William Tuckwell was eighteen years younger than Harding Newman, while Lewis Tuckwell was almost thirty years his junior. William Tuckwell's reminiscences were published in 1901, and as Owen Cheswick remarked, one of his foibles was "to pretend to be much older than he was." Lewis Tuckwell's Old Magdalen Days was not published until 1913. "Reminiscences" written so long after the fact should be treated with a degree of caution.

In his obituary published in Life and also in Modern Society, June 1882, Thomas Harding Newman is described as a doctor of divinity “with the finest of fine talents for low comedy and practical joking . . . he was from first to last brimful of tricks”. He “combined the functions of a doctor of divinity, organ grinder and buffoon . . . a Pickwick without embonpoint and with a sarcastic in lieu of a weak mouth”. The obituary writer adds, “he would buy an old picture at some one of the Wych Street shops for a song, touch it up in accordance with his intuitions, and exhibit it to his friends as a genuine old master”. Wych Street probably refers to an ancient medieval street in London, standing where the Aldwych is now, and known for its abundance of booksellers and antiquarian shops. Harding Newman was an established antiquarian, as indeed was his colleague Bloxam – it was, apart from Magdalen, the only thing they had in common. An avid collector, he even went so far as to purchase the old timber gates at Balliol and a seventeenth-century organ for his ancestral home in Nelmes, Essex. He was also responsible for repairing the Magdalen tapestries and installing them in the tower room.

Wych Street 1870

Throughout the obituary quoted by Foster and Sutherland, the anonymous author refers to "James" Harding Newman rather than "Thomas" - so it is unlikely that he is writing from personal knowledge or acquaintance with Thomas Harding Newman himself.

Foster and Sutherland state that "Wych Street probably refers to an ancient medieval street in London, standing where the Aldwych is now, and known for its abundance of booksellers and antiquarian shops". This is inaccurate. A contemporary reader would have immediately understood the reference - Wych Street was a famously disreputable area, known not for antiquarian shops but for pornographic ones. A letter to The Times decried "Holy-well Street and Wych Street, in which are shops the windows of which display books and pictures of the most disgusting and obscene character." The biographer is clearly suggesting that Rev. Dr Harding Newman thought it amusing to buy a pornographic picture in Wych Street and pass it off as a nude painted by an old master.

The various stories from old Magdalen days, then, remember Harding Newman as a forger, a competent artist, and also for Newman vs Griffith. For on November 26 and 7, 1873, he was before Justice Blackburn of the Queen’s Bench. According to Macray’s account, “In 1867 [T.H.N.] being then resident at Hornchurch, Essex, serious reports respecting his character reached the ears of the vicar of the parish, Rev. T. H. Griffith, who communicated with the College”. In October 1869, the College determined on an inquiry. Eventually, in November 1873, Harding Newman brought an action against Griffith for libel and slander with malicious intent. According to The Times’s legal report of November 27, 1873, Griffith had accused Harding Newman of “committing an unnatural offence”. By then, the statute of limitations had expired on the libel but Newman received £300 in damages when the jury found Griffith guilty of malice towards him.

He may have won his case, but the ongoing scandal had provided Magdalen with a reason to refuse Harding Newman a College living that fell vacant in 1870 and, in March 1873, the increase in his income required him, as was usual at the time, to resign his fellowship. Harding Newman left Magdalen under a cloud and with a sense of grievance: his forced resignation came months before his successful suit against Griffith to clear his name; his subsequent appeal (in 1874–5) against the injustice of the refusal of a living was rejected. If one takes all this into account, does it not lead to an alternative origin for the Rice portrait?

Griffith was accusing Harding Newman of being gay, which at that time was an imprisonable offence, The jury found in Harding Newman's favour and after finding Griffith guilty of malice towards Harding Newman, awarded £300 to the latter in damages. It is not clear what point the authors are seeking to make in referring to this case. Futhermore, there is no evidence that Harding-Newman left the college with any sense of grievance. According to his obituarist he had ‘inherited too large a private fortune to continue to retain his fellowship’.

Consider an Oxford don passed over for a clerical living by his college and known chiefly among his peers as an inveterate practical joker and buffoon. Add to that the indignity of being compared, merely through sharing the same surname, to the most charismatic theologian of his day, John Henry Newman: “not that Newman”, “the other Newman”. What better revenge than to come up with one last glorious practical joke that would implicate the College and perhaps touch, however lightly, the Cardinal’s associates?

There is no evidence that Thomas Harding-Newman carried any ‘sense of grievance’. According to his obituary in Modern Living, on the contrary, he found the confusion between the two Newmans very amusing and once sent a jocular poem to two elderly sisters who had mistakenly written to him instead of to John Henry Newman.His niece, Mary Allies, in a biography of her father, Thomas Allies, wrote: ‘At Oxford he [Thomas Allies] became intimate with the Rev. Thomas Harding Newman, of Magdalen, his future brother-in-law. Thomas Harding was a Newman by accident, for his father, Mr. Newman of Nelmes took the name of Newman instead of Harding. There was thus no relationship between Thomas H. Newman and John Henry Newman, only the difference of the letter T, and both were doctors of divinity after the approved Anglican fashion. This letter T led to many jokes caused by mistaken identity, and no one enjoyed them more than T. H. Newman.’ (Thomas William Allies by Mary H Allies, 1907).

A few years earlier A Memoir of Jane Austen had been published, and Harding Newman’s former colleague Morland Rice was known to be related to the novelist. Rice was also a close friend of Dr Bloxam, who had been curate to the other Newman in Littlemore before he entered the Church of Rome, and remained his lifelong friend. Jane Austen happened to be much favoured by the Cardinal, who, according to William Tuckwell, read Mansfield Park every year “to perfect and preserve his style”.

So, Thomas Harding-Newman, in order to satisfy an invented sense of grievance, sought to embarrass a friend of Cardinal Newman who was also a friend of Rev. John Morland Rice. Apart from the ludicrously obscure nature of this ‘revenge’, how would Thomas Harding-Newman explain this so-called plot to his stepsister, Eliza Hall Allies, a close friend and disciple of Cardinal Newman, or to other members of his family?

Why not go up to London to Wych Street and buy a canvas from roughly the appropriate period and “touch it up” accordingly, in the manner of the Andrews portrait of Jane Austen? Close examination of photographs of the Rice portrait indicates possible reworking around the mouth and eye areas. Harding Newman would have known he had to create a suitable provenance for the picture, one that required no paper trail but was based on family lore.

There is no evidence whatsoever of ‘reworking around the mouth and eye areas’ of the Rice Portrait. This is pure invention on the part of the authors, who have never seen, or asked to see, the picture.

We wonder how Thomas Harding-Newman would manage to find, in a pornographic shop, a painting which appeared so similar in style to that of Ozias Humphry that it fooled, amongst others: 1) Richard Walker, Regency expert at the National Portrait Gallery, 2) Conall Macfarlane, Director at Christie's Auction House, 3) Brian Stewart, Director of the Falmouth Art Gallery, author of A Dictionary of English Portrait Painters up to 1920 and a recognised authority on British portraiture, 4) Eva Schwan, one of the world’s top art conservators, who worked on restoring the painting over many months, 5) art critic and historian Brian Sewell and 6) Angus Stewart, President of the British Section of the International Association of Art Critics. All of these people agree the painting is the work of Ozias Humphry. In spite of the fierce controversy over the subject and the artist, no art expert has EVER suggested the Rice Portrait to be a late nineteenth century forgery by an amateur artist.

We also wonder how the Reverend Doctor managed to find, in a pornographic shop, a painting which looks so similar in style to the painting of Jane Austen's brother, Edward Austen Knight, now hanging at Chawton House:

How would Dr Harding-Newman have known that the painting was so similar in style to that of Edward Austen Knight? And how would he have known what Jane Austen looked like? He would have had no visual guide to Jane Austen's appearance aside from the engraving by Lizars, published in James Edward Austen Leigh's biography in 1869. This engraving was based on a watercolour by James Andrews which in turn was based on the sketch by Cassandra Austen, which is now in the National Portrait Gallery but at that time was still in the private ownership of the Austen family. As the authors state, ‘the nieces who knew her admitted was not “much like the original”. We know that the colour of Jane Austen’s hair was auburn - exactly the same colour as in the Rice Portrait.

His own stepmother had been a huge fan of Jane Austen. She could have been given the painting by Colonel Austen, who was possibly a neighbour, having lands in Essex as well as Kent, and who knew how much she appreciated his relative Miss Austen and her work. She then left the painting to her stepson Thomas Harding Newman who decides to give it to his friend Morland Rice who is, after all, related to the novelist. Rather than give it directly he asks Dr Bloxam, now ensconced in a Magdalen College living close by his friends the Morland Rices in Sussex, to intervene. A man much respected in Magdalen and the world outside, Dr Bloxam is not only a noted antiquarian with a considerable collection of paintings of his own: he is the nephew of Sir Thomas Lawrence, who also admired Jane Austen’s novels and was a contemporary of Zoffany. Harding Newman attributes the painting to Zoffany and tells the story of how his family acquired it to Bloxam, whom even the most suspicious mind would not doubt.

His step-mother was not just a ‘huge fan’ of Jane Austen, she had probably met her - her aunt, Ann Hawley, was known to have been a friend of the Austen family. There is no reason to doubt the provenance provided by Harding-Newman. As the author’s note, John Rouse Bloxam, who passed the portrait to John Morland Rice, was a noted art collector, and of course would have spotted a fake painted by Thomas Harding-Newman.

Then he bequeaths it to Morland Rice, but somehow forgets to formalize the arrangement. But his heir remembers and it is entrusted, like the earlier letter of provenance, to Bloxam to give to Rice. The scheme is ingenious, and almost foolproof.

Having come up with an elaborate and convoluted scheme to somehow embarrass Cardinal Newman (it’s still not clear to us how this would work) he ‘somehow forgets to formalize the arrangement’. In other words, according to this fantastical speculation, Thomas Harding-Newman went to the great lengths of buying a painting, expertly disguised it to look like a portrait of a young Jane Austen, managed to paint it in the style of Ozias Humphry, added Humphry’s monogram to the painting (detected by the conservator Eva Schwan and by Christie’s) added Humphry’s signature, the words Jane Austen and the date 1789 to the painting, wrote a letter in which for some unknown reason he then attributed the picture to Johan Zoffany, pretended it had been given to his step-mother by Colonel Thomas Austen and then didn’t even play the alleged prank.

While the alternative provenance sketched here is speculative, the evidence concerning Newman is not. Given his contemporary reputation and attested habits, should we not be cautious? In the end, the question is this: would you trust a picture from this man?

We disagree. The character of Rev. Dr Thomas Harding Newman presented by Foster and Sutherland is also speculative. The authors present a bitter, vengeful and resentful man who harboured a sense of grievance, none of which is borne out by the evidence. His obituary in Modern Society noted that he was "a thoroughly genial gentleman, who was always the best of good company, never better, perhaps, than after the second bottle of Magdalen port." According to Jackson's Oxford Journal, "Dr Newman was a man of high attainments in art, and a very popular member of the Athenaeum Club, and was also well-known in West-end society." He had a wide circle of friends and a large number of inhabitants of the parish were present at his funeral, according to the Essex Standard, who reported that he was "a true-hearted gentleman, kind, courteous, liberal and sympathising."

Thomas Harding-Newman may have been ‘brimful of tricks’. But scheming fraudster he most certainly was not.