Ozias Humphry (1742-1810)

Introduction

The Rice Portrait was once believed to have been painted by Humphry’s friend and rather better-known contemporary, Johan Zoffany. The painting was described as a Zoffany by a previous owner, Dr Thomas Harding-Newman, and this mis-attribution persisted until the early 1980s, which undoubtedly caused verification problems for previous owners, who were unable to reconcile the date, 1789, which was the date on the painting, as noted by Fanny Caroline Lefroy, with the fact that Zoffany was known to have been in India until August 1789. Furthermore there was no known connection between Johan Zoffany and the Austen family.

In 1985, Conall Macfarlane of Christie’s inspected the painting to value it for insurance and detected Ozias Humphry’s distinctive monogram of an H within an O on the painting. He recorded that the painting was ‘signed with initials’.

The eighteenth century artist Ozias Humphry is hardly a household name and there has been no catalogue raisonné of his work since the Life and works of Ozias Humphry, R.A. by George C. Williamson published in 1918. Yet in his day Humphry was an acclaimed and sought-after miniaturist and was also a fine painter in oils and later, in crayons. He painted the royal family and took commissions from many of the wealthy families of the day.

On 18 October 2003 an article appeared in The Times newspaper, reporting that the Rice Portrait was of Jane Austen and that Conall Macfarlane of Christie’s believed the portrait was painted by Ozias Humphry, causing long-time opponent of the Rice Portrait, Deirdre le Faye to write to Jacob Simon at the National Portrait Gallery accusing Conall Macfarlane, who had become a Director at Christie’s in 1991, of being ‘muddle headed’. She went on to say ‘do you know this Conal MacF? I assume he must be a new recruit to Christie’s, unaware of the background controversy’.)

Madeleine Marsh, who was carrying out research for the Rice family, wrote to the National Portrait Gallery after Conall Macfarlane’s valuation. She received a reply from Regency portrait expert Richard Walker. Previous to his employment at the National Portrait Gallery, Walker had been curator at the Palace of Westminster and official art advisor to the Government for 26 years. He replied: ‘I am sure you are on the right track with your attribution to Ozias Humphry. It fits very well with his style of painting and your research shows that he would have been a likely artist to have been employed by the family’. In the same year, 1985, the National Portrait Gallery published their directory, Regency Portraits, which was compiled by Richard Walker, in which he attributed the Rice Portrait to Ozias Humphry.

In 2007, Christie’s New York attributed the portrait to Ozias Humphry in their sale catalogue:

In 2010 conservator Eva Schwan spent several months examining and cleaning the Rice Portrait. Ms Schwan holds an MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art and a diploma in art conservation from France's Institut National du Patrimoine (INP) and has carried out work for many prominent art institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Musée National d'Art Moderne (Pompidou Centre) in Paris and the Courtauld Institute in London. She is a highly respected conservator. In her report she describes the painting as ‘probably the authentic portrait of Jane Austen by the British painter Ozias Humphry’ and includes images of Humphry’s monogram. Eva Schwan describes the technique of the painting as ‘astonishingly direct’ and observed that the artist worked with ‘great rapidity’, which accords with his biographer G. C. Williamson’s remark that ‘Humphry was an exceedingly rapid worker’. You can read Eva Schwan’s report HERE.

Ozias Humphry Biography

Ozias Humphry

Ozias Humphry was born on September 8th 1742 in Honiton, Devon. He studied under the miniaturist and portraitist Samuel Collins at Bath and while working in the city became aquainted with Thomas Gainsborough and worked in his studio. In 1763 he moved to London, where he lodged for a time with his mentor and friend, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds encouraged his talent and procured him his first royal commission, which yielded the then-enormous sum of 100 guineas. In London, Humphry also studied with Johan Zoffany and met many of the other prominent artists of the day. Ozias Humphry’s greatest talent was as a miniaturist, and after he was commissioned by George III to paint the queen, he was in great demand as one of the leading miniaturists of the day. It was a great misfortune for Humphry that he fell from his horse in London in 1771 in an accident that badly damaged his eyesight. After this incident he suffered increasingly frequent spells of blindness and eventually lost his sight altogether in 1797.

No longer able to concentrate fully on miniatures because of the periodic difficulties with his eyesight, Humphry set about painting ‘in large’ in oils. In 1773, he set off to France and Italy with his great friend George Romney where they remained for four years. On the way they stopped at Knole House, Sevenoaks in Kent, where John Frederick Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset, Humphry’s earliest and most generous patron, commissioned him to copy various famous Italian paintings. It is noteworthy that the familes who patronised Humphry - the Dorsets, the Cravens and the Berkeleys - also employed the services of the attorney Francis Austen.

Romney influenced Humphry’s style and some of his works were subsequently mistaken for Romney’s, most famously The Ladies Waldegrave as Venus and Juno (see below).

Humphry was unable to achieve the same amount of work as he had with his miniatures. He complained to his brother that he was unable to earn an adequate living from the commissions he was receiving in England and so, tempted by the stories of the fabulous riches to be made in India painting nabobs and princes, he decided to try his luck and set off for Calcutta at the end of 1784. But his Indian venture failed to produce the success that other artists achieved. In competition with Zoffany in full-sized oils and unable to compete with John Smart in miniatures due to his failing eyesight, Humphry slid into depression. To cap it all, a large and lucrative commission for the Nabob of Oudh at Lucknow was not paid, the injustice of which consumed Humphry for the rest of his life. Ozias Humphry left India out of pocket and in ill humour in June 1887 and by the end of the year he was in back in England and in need of money and commissions.

From his original status as an Associate of the Royal Academy, Ozias Humphry was promoted to full fellowship in 1791 although he was in fact signing his paintings as ‘R.A.’ long before this date. Shortly after receiving his fellowship, Humphry’s eyesight failed him while painting miniatures for the Duke of Dorset and he switched to painting in crayons; a portrait at Knole House is inscribed as being the first portrait in crayons painted by Ozias Humphry, R.A. begun in May and finished early in June 1791. In 1792 he was appointed Portrait Painter in Crayons to His Majesty, on which occasion he showed the king his portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Dorset amongst others, which were graciously received and very highly approved of, according to the Morning Herald. But Humphry’s eyesight continued to deteriorate and in 1797 he went completely blind. No longer able to paint, he lived out the remaining years in quiet seclusion.

Ozias Humphry never married but had an illegitimate son and heir, William Upcott, who became famous as an early collector of autographs and as the discoverer of the lost diaries of John Evelyn. Contemporary accounts of Ozias Humphry describe a kind man with a quick temper, something of a snob and inordinately proud of his grand patrons, especially the Royal family. He was clearly also devoted to the family of his clergyman brother William Humphry as well as to his own illegitimate son, William Upcott, and was a popular member of a circle that included many of the great artists of his day. This was demonstrated by the steady support they gave him after the accident that so blighted his career. Ozias Humphry died in Hampstead in North London, in 1810.

Ozias Humphry and the Austen Family

We now know that Ozias Humphry was closely linked to the Austen family.

In 1770 the Duke of Dorset appointed Ozias Humphry’s brother William as Vicar of St Peters Church, Kemsing & Seal, close to Sevenoaks and Knole House. At Seal, William Humphry was a neighbour of William Hampson Walter, step-brother of Jane Austen’s father, George. In 1798, it was William Humphry’s wife, Elizabeth Humphry, who wrote to George Austen at Steventon Rectory to inform him of his step-brother’s death. Jane Austen immediately wrote to her cousin, Philadelphia Walter: As Cassandra is at present from home, You must accept from my pen, our sincere Condolence on the melancholy Event which Mrs Humphries Letter announced to my Father this morning.

Francis Austen

George Austen’s uncle, Francis Austen, was a wealthy lawyer in Sevenoaks. He was also agent for the Duke of Dorset and in 1780 the Duke of Dorset commissioned Ozias Humphry to paint a portrait of Francis Austen.

Francis Austen wrote to Humphry to tell him how pleased he was: ‘The Duke of Dorset does me great honour in wishing to have my picture and as tis to be your hand I feel myself very happy with the thought of this being in his Grace’s collection and will submit myself to sit for you whenever will be convenient to yourself’. This painting now hangs at the Graves Gallery, Sheffield.

Jane Austen’s brother Henry, recalled the painting: ‘In his picture over the chimney the coat & vest had a narrow gold lace edging, about half an inch broad, but in my day he had laid aside the gold edging, though he retained a perfect identity of colour, texture make to his life’s end.’

John Hubback, grandson of Jane’s brother Francis, lived with his grandfather as a boy. He later recorded that great-uncle Francis Austen was a regular visitor to the Austen family home: As a boy at Steventon Rectory, before he [Francis Austen] went to sea in 1788, he was a great favourite with another Francis Austen, his grandfather’s brother, a frequent visitor of the Rectory.

You can read more about Jane Austen, great-uncle Francis Austen and Ozias Humphry in this exerpt from Terry Townsend’s book Jane Austen’s Kent, published in 2015.

It is well documented that Jane Austen visited her great uncle Francis Austen at his home, the Red House in July 1788 along with her mother and father and her sister Cassandra where they were joined by the Walters and by Francis Austen’s son, John. It was probably during this visit that Francis Austen commissioned Ozias Humphry to paint portraits of Cassandra (see below) and Jane Austen. There is nothing surprising in this, portraits were the means by which the wealthy middle class of which Francis Austen was a member, made their mark.

The Rice family has always believed that after the portraits of Cassandra and Jane were commissioned in the summer of 1788, Ozias Humphry stayed at Godmersham Park that autumn, at which time he executed sketches and drawings of backgrounds in the park. There is evidence for him being there on 04 October 1788 because a letter written to Ozias in London was redirected to him at the Sevenoaks residence of Stephen Woodgate, the brother of Mrs Humphry. This letter is held at the Royal Academy in London.

On the 7th of October 1788, Edward Austen was 21 years old, and again family tradition has it that he had returned from the first leg of his Grand Tour for his coming of age celebrations with his adoptive parents. His own portrait places him within the Godmersham grounds in front of a large oak tree, with the Godmersham temple folly in the background.

Jane's background in the Rice Portrait includes what we believe is the river Stour that flows close to Godmersham house. In both pictures the same autumnal colours are used, as well as the depiction of stormy skies. It's also interesting to note the similarity in stance of the subjects in these portraits; the angles of Edward’s cane and Jane’s parasol being almost identical.

Over time all the Austen family artefacts passed to different family members and the three portraits are no different. Jane Austen’s portrait, after staying in the family for two generations, was given to a family friend who may have known Jane personally. (You can read more about this in the Provenance Section.) Edward’s portrait remained at the home of his adoptive parents, Chawton House, which Edward inherited until 1952 when it was sold for £24 in an effort to raise monies to pay for death duties. Later the painting passed to the Jane Austen Society and hung in Alton’s council offices before moving to Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton. It was too big for the cottage and also in need of restoration so the owner of the Rice Portrait, Anne Rice began a campaign to raise funds for its restoration, encouraging members of the wider family, notably Lady Mountbatten, to contribute. In 2011 the painting returned to grace the dining room at Chawton House where it remains today.

A missing portrait of Cassandra?

In 1952 Mrs Harrison wrote to Austen scholar R. W. Chapman, advising him that she owned a portrait she thought may be of Jane Austen and enclosed a photograph. Mrs Harrison was a direct descendant of great-uncle Francis Austen and her grandfather had inherited the family home of Kippington. We don’t have Mrs Harrison’s letter or the photograph but Chapman consulted a member of the Austen family, Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh and his reply to Chapman is now in the Bodleian Library. (See Primary Evidence Section.) Austen-Leigh told Chapman that as Mrs Harrison was from the Kippington stable and as the ‘Zoffany’ (as the Rice Portrait was then known) had belonged to a Kippington Austen ‘there seems quite a probability of it and the Zoffany being the same person’. It clearly did not occur to him that this portrait could be of Jane’s sister, Cassandra Austen.

Mrs Harrison also owned miniature portraits of various members of the Austen family which were the subject of Deirdre Le Faye’s article in the Book Collector, written in 1996. (See HERE.)

After the death of May Harrison’s only son in 1940, the entailed Kippington estate passed to her distant relatives, the Knights at Chawton.The widowed Mrs Harrison moved to France where she died intestate in 1980 and the whereabouts of her painting is unknown. Her nephew later recalled a painting at his aunt’s house of a girl in a white dress but did not know what had happened to it.

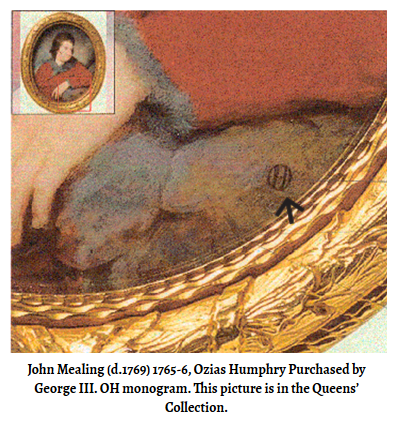

Ozias Humphry’s monogram

Humphry was in the habit of signing paintings with his distinctive OH monogram, a capital ‘H’ inside a capital ‘O’.

Some examples are shown below.

George Romney influenced Ozias Humphry’s style and works by the two artists were so similar stylistically that they could easily be confused. Compare, for example this portrait of William Beckford by Romney (left) with the portrait of Edward Austen Knight by Ozias Humphry (right)

Upton House © NTPL William Beckford

Edward Austen Knight

One portrait, The Ladies Waldegrave as Venus and Juno which had been sold at auction as a Romney was the subject of a seven-day court battle in May 1917, with many experts pronouncing that the painting was by Romney, only for the matter to be resolved when the plaintiff produced a sketch of the painting which had been discovered in the archives of the Royal Academy, with Ozias Humphry’s distinctive monogram of an H within an O in the bottom right-hand corner. The Times newspaper remarked in an editorial: 'the lesson for experts from these and other cases is the old lesson - not to be too "cocksure" in their opinions, and still more, not to be too positive in stating them.'

The Ladies Waldegrave as Venus and Juno - private collection

The sketch with Ozias Humphry’s monogram

Ozias Humphry’s monogram on the Rice Portrait

Humphry’s monogram was detected on the Rice Portrait in 1985 by Conall Macfarlane of Christie’s when he carried out an examination of the portrait for insurance purposes. He noted in the valuation report that the painting was ‘signed with initials’.

In 2010 we decided to have the portrait cleaned. Previous interventions had not been helpful in the light of new techniques and the picture needed considerable work. We sent the painting to Paris to be cleaned by the highly respected conservator, Eva Schwan. (Eva’s resumé is very impressive, she holds diplomas in painting restoration from both the Courtauld Institute and France's Institut national du patrimoine.) Over many months she carried out painstaking cleaning and restorationwork, millimetre by millemetre, on the portrait. Her conclusions are of immense significance and we are most grateful for her permission to place them on our website.

Eva has produced three reports. The first report, dated 31 March 2011 is THE REVEALED MONOGRAM OH.

In this report Eva Schwan says: ‘Undoubtedly, one of the most significant discoveries of our cleaning has been the revealing of Ozias Humphry’s monogram OH in the left corner of the painting. Altough damaged by harsh cleaning and other traumatising interventions in the past, the initials are clearly visible.’

A Conversation Piece

During his extensive research into the Rice portrait, Mrs Rice’s brother, Robin Roberts, discovered the catalogue of a three-day sale, which had taken place at the previous home of Jane Austen’s brother, Edward Austen Knight, Godmersham Park in Kent on June 6th 1983. Godmersham Park had been bought in 1936 by a Mrs Elsie Tritton. An avid collector, on her death Christie’s held a three-day sale and the catalogue, beautifully illustrated, was most impressive. There were various lots at the end of the sale containing a photograph of Edward Knight and pictures of the family which confirmed that the Trittons had also bought, with the house, the residue of the Knights’ family possessions.

One picture in particular attracted Robin’s especial interest, described in the catalogue as belonging to the English school, circa 1780. It shows a gentleman and his wife, with their four children standing around an oval dining table in a small dining parlour. We believe that this little painting is of George Austen, his wife Cassandra and four of the Austen children - Cassandra, Jane, Edward and Francis, painted circa 1780 by Ozias Humphry R.A. as a commemorative picture to celebrate the fact that his cousins the Knights had decided to adopt Edward. You can read more about the picture HERE